My parents and most of their friends were immigrants, Polish Holocaust survivors who spoke a mingling of languages-Yiddish, Polish, German, Hebrew. Sometimes their sentences would begin in one language and end in another, the conversation sprinkled with mysterious words that I couldn’t understand, sounds that scratched my throat when I tried to imitate, syllables that danced away from me. Polish, my mother said, was a language that could break your tongue.

My parents and most of their friends were immigrants, Polish Holocaust survivors who spoke a mingling of languages-Yiddish, Polish, German, Hebrew. Sometimes their sentences would begin in one language and end in another, the conversation sprinkled with mysterious words that I couldn’t understand, sounds that scratched my throat when I tried to imitate, syllables that danced away from me. Polish, my mother said, was a language that could break your tongue.

I mumble random words, alphabets of a lost

tongue, alert for the perfect lexicon that will tell me

who I am, the language that will free me from longing

and loneliness: Zaide, grandfather, l’chain, faith.

Before I was a writer, I was a reader. My mother’s father was a journalist who treated her, she said, like a son, taking her with him to political meetings and encouraging her intellectual development. She had the advantage of attending a Jewish school for girls, where she was sheltered from prejudice and encouraged to be smart and accomplished. She loved books and took me frequently to the local library. My ambition was to go through the shelves alphabetically reading every book. Maybe that was the seed of my writing life.

Or maybe the seed resided with my father, a tailor by profession, who could fashion a suit of clothes from start to finish, sew a dress from collar to hem. He would enter a conversation first with a touch of one’s sleeve, a comment on the quality of the material. My father was a storyteller who paid attention to detail. When he spoke, he would spin the past into a movie I could see behind my eyes. He talked about his life in Poland before the war, his large family of six siblings, the lakes, and cherry trees of his youth. He spoke of the war in a glazed way, at a distance, the way victims of trauma do when they remember.

He is inside the telling of his story,

his body far away, hidden under a mattress,

jumping off a train into snow,

hiding potatoes in his pockets.

We dug a trench. Then we filled it up.

Every day. Marching there and back

until it was dark. We ate cold soup,

not soup, water. Nothing.

How do we become who we are? I think, surely, my immigrant background was an influence in becoming a writer. Until I started kindergarten, I spoke no English. The demographics of my neighborhood and school were primarily Chicano with a Spanish speaking population, so I was twice removed from a language I could understand. I was isolated and quiet. I remember an incident in second grade when I gave an oral report about my pet and said kenery instead of canary, and everyone laughed. My mother cooked an artichoke and declared it inedible because it was too tough. She didn’t know to only eat the tender part. Now, as I write, I notice the previous sentence is in my immigrant vernacular, not quite grammatical, not quite correct. Perhaps this affords me some freedom as a poet, the ability to experiment with language, to write outside the box. Dialogue, conversation, has always been part of my poetry. I am attracted to speech, to the music of dialects.

Gai platz, the uncles would shout in unison, no one

listening. Gai mit dein kop in drerd,

Summer nights or in the kitchen when the kinder were pretending

sleep, they’d murmur Gedainst? Remember?

and their voices would take on a tone

………the English would fade away like smoke

until only the Yiddish remained, and we were foreigners

in our own houses, with strangers for parents..

I always felt my family had a story and that perhaps it was my obligation, my destiny and desire to tell it. But I wasn’t at first drawn to poetry. I thought I might write a novel or a memoir. Although poetry, I felt, had an emotional depth, a precision I couldn’t find elsewhere. I didn’t know I could write poetry. I thought it was for academics, that I wasn’t educated or smart enough to be a poet.

Los Angeles was a sprawling desert where I felt lost. I moved to San Francisco to find a community of writers, just in time for the arrival of the Women’s Movement that was barreling around the corner, and it hit me head on. Women began to publish poets who had been excluded from recognition. I was an English Lit major, and we were required to read the Norton Anthology of English Literature, the academic bible, which consisted of primarily white male writers. Women began to protest by publishing their own small presses and magazines–Kelsey Street Press in Berkeley, Lilith, Calyx. Anthologies, including No More Masks edited by Ellen Bass, introduced me to Anne Sexton, Gwendolyn Brooks, Adrienne Rich, Nikki Giovanni, and so many others. These poets spoke to me in an intimate, visceral way that I hadn’t experienced before.

I took a class at Intersection for the Arts in North Beach with Diane di Prima. I began to write poetry secretly in my journal. I must have slipped the secret to my roommate because she told her friend, Stephanie Mines, a local poet who ran a women’s workshop and salon in her storefront apartment in Noe Valley. Stephanie asked me to join and when I did, I suddenly had a community, a poetry family who would listen, comment, and encourage. We read at bookstores, contributed to Stephanie’s Noe Valley Anthology and began to stretch in confidence and craft. I joined a women’s poetry workshop with Diane di Prima at Intersection for the Arts in North Beach. With a friend, I launched a magazine, Room, A Women’s Literary Journal. To get started, we produced a benefit reading with Stephanie Mines, Kathleen Fraser, Susan Griffin, and Judy Grahn. The cost of admission was about $3.00, and the room was packed! We went on to publish the early work of Sharon Olds and Kay Ryan. We published older poets who had been overlooked and interviews, including one with Mary Mackey. I enrolled in a Feminist Poetics course with Kathleen Fraser, who subsequently wrote a curriculum book that included poetry and essays by the women in our class. I had found my people and my place.

The next big event in my writing life was the discovery of California Poets in the Schools. I had gone on in college to get a teaching credential, because what else, I thought, could a woman do for a living? I loved working with children, but I felt uncomfortable and unsatisfied. Through news from the grapevine, I found myself at meeting with Carol Lee Sanchez. Poet-teachers sat on the floor and leaned against the walls drinking coffee and smoking cigarettes. I was welcomed and encouraged to become a poet-teacher—which I did. My teaching life has been parallel to my writing life, and one has informed the other.

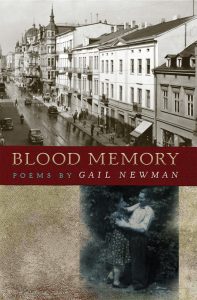

My new book, Blood Memory tells my parent’s story. Why did it take so long to write the story that was inside me? I became a poet, a teacher, a wife. I learned to cook and make a garden. I made a child. I went to school meetings, wrote grants, bought a dining table, a set of wine glasses, a house. And still, I did not write my family’s story. Why? I tried when I was young and could not do it. I was discouraged by others, who said, So much had been written about the Holocaust already. As if it was irrelevant, old news. I did not know how to write about the unspeakable. I had to learn to step back and let the story unfold without interference, to keep my emotions leashed, so the reader could respond-feel, see, be moved or horrified or hopeful.

When my father died, I began to write about him. The flood gates were open. I went to Poland with my husband and The March of the Living to find the past. I found my father’s house and his work papers from the Lodz Ghetto. I went inside the run-down building in Lodz that was once the ghetto where my mother lived in one room with her brother and my grandmother. I went to the graveyard in Auschwitz where my grandmother was buried. I saw the forest where the ashes of the dead fell. I thought about my childhood.

they’d murmur Gedainst...

and the English would fade away like smoke

until only the Yiddish remained, and we were foreigners

in our own houses, with strangers for parents.

Some days, now, I can’t believe the state of the world. It seems we haven’t come as far as we thought. Through this time of Pandemic, bigotry, global warming, I keep my parent’s stories close to my heart. I think of them every day-what they went through, how they survived.

I think about poetry, kindness, the earth. Resilience. How much we have of beauty. Why we need to remember the past. Elie Wiesel said–

Whoever listens to a witness, becomes a witness.

Gail Newman is the author of Blood Memory, from which the poetry excerpts above were taken. She has worked as an arts administrator, museum educator at the Contemporary Jewish Museum, and CalPoets poet teacher and San Francisco Coordinator. She was co-founder of Room, A Women’s Literary Journal and has edited two books of children’s poetry: C is for California and Dear Earth. A collection of her poetry, One World, was published by Moon Tide Press. A child of Polish Holocaust survivors, Gail was born in a Displaced Persons’ Camp in Lansberg, Germany, and immigrated to the United States with her family where they settled in Los Angeles. She lives in San Francisco with her husband. “With its publication, “Blood Memory” joins the pantheon of exceptional writings.”–Joan Gelfand, Wilderness House Literary Review 16/1