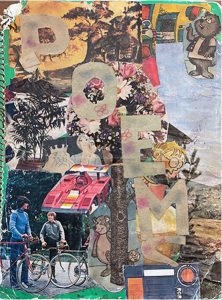

It was a standard bright-green notebook, three-hole-punched and lined. My mother and I spent the afternoon cutting out pictures I liked from magazines and newspapers and gluing them to the front. The collage covered nearly all the green—pictures of Cat in the Hat, Mr. Peabody and his dog Sherman, Alvin and the Chipmunks, Yogi Bear, and random images I cut out from magazines: two boys with 1970s haircuts and too-tight turtlenecks on ten-speed bikes, an orange transistor radio, and random photos of nature—trees, roses, mountains. We cut the word “Poems” from dark blue construction paper and glued it atop the collage. I drew pink flowers on the words. Bits of green peeked through the corners of the notebook.

It was a standard bright-green notebook, three-hole-punched and lined. My mother and I spent the afternoon cutting out pictures I liked from magazines and newspapers and gluing them to the front. The collage covered nearly all the green—pictures of Cat in the Hat, Mr. Peabody and his dog Sherman, Alvin and the Chipmunks, Yogi Bear, and random images I cut out from magazines: two boys with 1970s haircuts and too-tight turtlenecks on ten-speed bikes, an orange transistor radio, and random photos of nature—trees, roses, mountains. We cut the word “Poems” from dark blue construction paper and glued it atop the collage. I drew pink flowers on the words. Bits of green peeked through the corners of the notebook.

“It’s your first book,” my mother told me. “Write your poems and stories in here.”

We made the notebook in 1978, when I was eight years old and my mother was 35. My third grade Language Arts teacher, Mrs. Wright, told us we needed a notebook for our class writing, and it was my mother’s idea to help me decorate it to make it personal. I used the notebook to write poems both in and out of school, with titles like “My Kitty,” “The Kiss,” “About Ballet,” and a story about the summer we moved from Florida to Chicago called “The Trip.” A section with limericks, one called “Willy” and this one, “Liz,” was centered on the page:

There once was a girl named Liz

who wanted to go into showbiz.

She went in May

Then was in a play

And she came out with a friz.

I loved being Mrs. Wright’s student, and I didn’t know then I would become both a teacher and a writer. I’m a full-time high school English teacher, a university adjunct instructor, and a writer with full-time writing deadlines. Now, instead of stories about kittens and ballet, I write about my decades of experience as a high school English teacher, and essays about family. I’m working on a project of transcribing and writing about my grandfather’s letters he wrote from a ship in the Pacific Ocean during World War II. I also write about Israel and Palestine; specifically, what it was like living in Jerusalem in the 1990s as a graduate student and the relationships with the Palestinians, Israelis, and Armenians I met there.

I’m happy to be both a writer and a teacher, though both are demanding. In fact, I’m glad I was already writing and teaching when I first heard Sandra Cisneros talk about the difficulty she had maintaining a writing and teaching life, happy no one told me it would be hard to find time to write when I was a new teacher. If they had, I might not have gone into teaching, or I might not have become a writer.

“It was very hard for me to find time to write when I was teaching high school students,” Cisneros said before reading her story, “Eleven,” at a Lannan Foundation reading in Los Angeles in 1996. In her opening remarks, she talked about the publication of the story, a short piece about a girl who feels humiliated at school on her eleventh birthday. I’ve been teaching the story to ninth-graders for years as a way to talk with them about empathy and compassion. In the video, just before reading her story, Cisneros confesses to the audience that finding time to write while teaching high school was so arduous for her that she eventually stopped teaching and lived for a while with her brother, who paid her bills, so that she could focus on her writing.

Creating time to write means creating the conditions to write, which is to say, it means having more of a disciplined life than I’d like. During the school year, I leave home at 6:30 a.m. Mondays through Fridays, and return around 5:00 p.m. On the days I teach at my university job, I don’t get home until 10:00 p.m., then leave again the next morning at 6:30 a.m. for the high school. During the school year, I work about 80 hours a week on teaching and writing (40 hours for each). In the summer, when I’m not teaching, I work 40 hours a week on my writing. The joy of having only one full-time job—writing—each summer is priceless.

Part of the challenge of being a writer who teaches is that I love teaching, and I love writing. Both feel like callings; neither are simply day jobs. In many ways, the calling to be both a teacher and a writer crosses boundaries and merges, one into the other. I’m constantly reading and teaching stories like Cisneros’s “Eleven,” pieces that remind us how literature can help us deepen our capacity for love. I also try to reach people through my own writing and at the same time, I want to encourage my students to do their own writing, too, like Mrs. Wright, and my mother, did for me in 1978. I’ve worked through issues by writing about them: conflicts with friends, old loves, family strife, ideological shifts. It’s always my hope when teaching writing to my students that they might also work through the conflicts they’re experiencing in their lives. For instance, “My Trip,”one of the stories in the 1978 green notebook, was about the distress I felt moving from Gainesville, Florida to Evanston, Illinois when I was eight years old:

My first trip started when I lived in Florida. My Dad got a better job in Chicago. He had to tell me. When he told the family that we were going to move, I got really mad. My Mom and Dad went to Chicago to look for our new house. They finally found one and it had a basement and an attic. When we lived in Florida, we didn’t have a basement or attic. And I never saw snow there either.

It sounds like child’s play, but I remember working through these complex emotions at the time—moving across the country to a new city with a different climate, leaving friends I had at school and in our neighborhood. I was mad and frightened, so I wrote about it and moved through it. I turned the experience into a story with the help of my teacher. Now, I try to be the same kind of teacher I had—to encourage my students to write about things they are struggling with, to turn their struggles into stories as they move through their emotions.

Creating time to write means writing mostly on the weekends. Maybe some evenings during the week if I’m not at the university. It means what Paul Theroux confessed once in an interview: “Writing is not compatible with anything—its utter self-absorption is generally destructive to family life and friendships,” he said. “And yet I find it joyous.”

On most Saturday and Sunday mornings, creating time to write can mean making my to-do list on a post-it note that includes things like “work on essay,” “walk,” “read,” “groceries,” “work on poetry manuscript,” “call Mom,” “return to essay.” The writing is predictably slower during a school year than during summer break, just as it will be slower on a weekday than a weekend, and it takes time to get into a head-space where I can write.

Teaching is both exhausting and an adrenaline rush, and the multi-tasking one needs to do to stay on top of the workload is far more complicated than the multi-tasking one might choose to do. Most high school teachers teach five classes and multiple age levels (ninth through twelfth grade) and various courses. We have been dealing with cell phones in schools for years, as well as heightened anxiety and depression among teens, and their increased dependence on social media. School shootings have increased. Educators are grappling with how to navigate the rapid pace in which artificial intelligence has infiltrated the classroom, making it harder for students and teachers to focus on learning. Needless to say, I have to train my mind to slow down after teaching so that I’ll be able to write. And I try to turn these classroom issues into stories as I work through them.

On weekends, I often write during breakfast and lunch, like I’m doing right now. If I’m unable to write for whatever reason, I’ll work on submitting finished pieces for publication. So in a sense, I’m always doing something with the business of writing when I’m not teaching, whether I’m actually writing or not. How much writing I can expect to do also depends on where I am in the piece of writing. Early drafts require more concentration and focus, sometimes hours of unstructured time, which can be difficult to create, for instance, during periods of heavy grading or parent-teacher conferences, while later drafts are easier to jump back into if I have a random half hour here and there.

I’m also frequently juggling multiple writing projects, and am at different stages with each. Often, I feel like a gardener with different kinds of plants that grow at different speeds—the roses may grow taller and the irises might grow faster, and the herbs, the basil and rosemary and cilantro, may grow differently, too. Some require more attention than others, but they all need watering.

Having multiple writing projects is also like having hundreds of students (I teach roughly 125 high school students each year and approximately 50 college students). Each one is its own universe, each with different needs and wants.

Ultimately, being a writer—creating the time to write—is about more than the writing itself. It’s about what happens when you write. It’s about turning a problem or an event into a story. It’s what Tim O’Brien called “putting one’s free time into an experience.” Writing isn’t just something I do, but a place I like to inhabit, a space where I get to know myself better, where I can feel grounded, which is why it can take time to get there. Once I’m in that place, time moves neither slow nor fast. I exist inside of time itself, inside the present moment. And no matter what I’m working on, I visit versions of myself and other people, too, at different stages of my life and in various places. Whether it’s the essay I wrote last year about taking my parents to The Louvre in their old age, or a piece about what it means to teach high school students in the age of artificial intelligence, or an essay about when I lived in Jerusalem in my twenties, I’m constantly sorting through a rolodex in my mind of my life, sifting through memories and experiences that have made me who I am.

While writing this essay, in fact, I’ve revisited my eight-year-old self who moved from Florida to Chicago. I remember how scared I was. As the last of the boxes were placed onto the moving truck, I took a black marker from one of the movers and wrote on my bedroom wall, “This will always be my room.” I drew a heart around what I’d written like two lovers carving their initials in an old oak tree trunk, and cried from the backseat of our station wagon as we pulled out of the long driveway where I’d learned to ride my bike, heading for the highway where we’d cross multiple state lines over the next two days. I was leaving my home for a new one, and didn’t know then that I would write about it, like I’m doing right now still, decades later, analyzing what it meant for my eight-year-old self to leave one home for another, a child who didn’t yet understand if home was with my family, wherever we were, or if it was the physical space of walls that mattered.

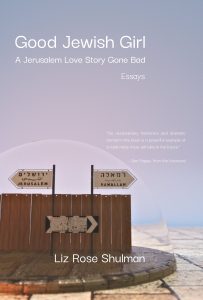

Looking back now, I realize that even as an eight-year-old, I was grappling with the whole notion of home and place, that I’d eventually turn the experience of moving into the story “My Trip,” in my decorated green notebook. Even later, in my book about Israel/Palestine, Good Jewish Girl: A Jerusalem Love Story Gone Bad, I’d struggle again, on an entirely new level, about what an ideological home and place can mean. And this kind of struggle has found its way into this story, too. I had created time to write and reshape my feelings into narrative form. All writing requires me to do this, whether I’m eight years old, or now, at fifty-five. I have to create the time I need to write about what is most important to me.

Next week, in fact, I’ll be teaching Cisneros’s “Eleven” to my ninth-graders again. I hope the story—indeed all the stories we read and all the stories we write—will help them learn about themselves and who they are in the world. I’m sure I’ll go home that day wanting to write—the inevitable and wonderful cross-pollination of being a writer and a teacher.

Liz Rose Shulman is the author of Good Jewish Girl: A Jerusalem Love Story Gone Bad, published by Querencia Press (2025). Her writing has also appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The Boston Globe, HuffPost, Slate, Los Angeles Review, and Tablet Magazine, among others. She is currently working on a book of stories from the high school English classroom. She teaches English at Evanston Township High School and in the School of Education and Social Policy at Northwestern University. She lives in Chicago. Visit her at lizroseshulman.com.

Liz Rose Shulman is the author of Good Jewish Girl: A Jerusalem Love Story Gone Bad, published by Querencia Press (2025). Her writing has also appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The Boston Globe, HuffPost, Slate, Los Angeles Review, and Tablet Magazine, among others. She is currently working on a book of stories from the high school English classroom. She teaches English at Evanston Township High School and in the School of Education and Social Policy at Northwestern University. She lives in Chicago. Visit her at lizroseshulman.com.