Alone, on long walks, the memories still come to me, arising out of the streets of Chicago or along the pilgrim’s path of Santiago, blurred but pungent, those intimations surface of days and nights in the land of the Mandinka and Wolof. They appear, like apparitions, unannounced, one calling forth others, bringing with them emotional chords long buried, and the lessons I learned living among the farmers of the Sine Saloum. There, alive on the periphery of my mind, I can see the sandy paths through the savannah, the smoldering sun, the baobab branches clawing at the sky, the children, mouths wide open, running about to catch the first drops of rain.

Alone, on long walks, the memories still come to me, arising out of the streets of Chicago or along the pilgrim’s path of Santiago, blurred but pungent, those intimations surface of days and nights in the land of the Mandinka and Wolof. They appear, like apparitions, unannounced, one calling forth others, bringing with them emotional chords long buried, and the lessons I learned living among the farmers of the Sine Saloum. There, alive on the periphery of my mind, I can see the sandy paths through the savannah, the smoldering sun, the baobab branches clawing at the sky, the children, mouths wide open, running about to catch the first drops of rain.

Though I would do little to alter the daily struggles of the Senegalese, they would, in return, have a lasting influence on my future life. I would not realize it at the time, but my education as a writer began in that small farming community twenty miles from the Gambia River.

Fresh from a failed attempt at acting in Chicago, fleeing Reagan’s America and the tumult of my sexual life, I joined the Peace Corps. With little training in community organizing or agriculture, I landed in a devout Muslim community of some five hundred souls in the southwestern corner of Senegal.

It didn’t start out well.

After the first few weeks, it was obvious how utterly unprepared I was for life in rural West Africa, not to mention how naïve I was to imagine that someone like me, all of 23 years old, with a theatre degree, could possibly help these subsistence farmers and their families.

Every day I sat under a mango tree and observed the Senegalese go about their daily work and devotions to Allah without complaint, and without electricity or running water. I watched as women labored from dawn to night: collecting firewood, cooking and cleaning, making clothes by hand, caring for children and the sick, tending their animals, hoeing their patches of land, and twice a day hauling water up from deep wells and carrying it across the village. With the men, I tried to help them, as they weeded their fields, squatting for hours in the heat of the day, but they just laughed and walked me back to a tree. At night, in the shadows, the hungry waited with bowls for dollops of rice and scraps left from the evening meals. And when the rains did not come, the men prayed at the mosque late into the night, asking me to join them.

We were told, of course, that it would be difficult and that it would take time to learn the language and initiate development projects. But culture shock quickly turned into shame. How cruel and patronizing to send someone with so little to offer. People here were in such need and so eager for assistance, and yet, I shuffled about with my notebook, making more work for the women, and slinking back to my hut each night. What was I, but nothing more than a shill for the promotion of US power and its corporate interests?

Embittered and disillusioned, but too terrified to consider quitting, I retreated from the village, taking long walks into the savannah or sitting inside my mudbrick hut, studying French and Wolof vocabulary, reading novels, and writing long letters to everyone I could think of.

Though I felt useless to the Senegalese, in the letters I wrote, I recounted my experiences and observations of everyday life as a traveler would, detailing encounters with holy men in the savannah, describing wedding ceremonies, farming techniques, acrobatic dancing, children’s games, and the birds I spotted in the bush. Fascinated with learning Wolof, a language with roots in ancient Egyptian, I shared my discoveries of new words and expressions, words to my surprise that had traveled into English via Jazz musicians and Beat poets, like the verb degg “to understand something from experience.” Or, my favorite word, “hep” “to see clearly,” which if used with the suffix, kat makes the famous word of the 60’s counterculture, hepkat, a person with vision and authenticity. Other times, my mood shifted, and out of despair, I would describe the crumbling roads, people with profound leprosy begging at the markets, or the countryside littered with failed development projects.

I wrote in a journal, of course, but in letters I felt a sense of responsibility to report what I had witnessed, to educate, to dispel myths about Islam, Senegalese culture, and Africa in general. Writing was a way for me to re-engage with village life, giving me a reason to ask questions, helping me to learn so that I might know how to better help the community. What I observed, what I experienced, and what I wrote mattered, even if it was only to my parents, a few friends, and a professor at college.

And I read thick, dog-eared novels, handed down from volunteers who had read them before me, as if the books themselves were a part of a rite of passage. I escaped into the 19th-century cities of Paris and Moscow via Zola and Dostoyevsky, lived the adventures at sea of Conrad and Melville, and soared with the prose of Tolstoy and George Eliot. Spellbound by their voices, I fell into their labyrinthine narratives, losing myself and the world outside in their detailed depictions of street life and landscapes. Yet what captivated me in these classic novels of social realism and protest was the writer’s insight into human emotions and the mind, especially as characters confronted moral and spiritual questions. Isolated and insecure, I identified with these characters, and in their soul-searching, I heard mine. In these books, writers not only created worlds in which readers could travel, but they also inspired readers to explore the interior realms of their psyches.

Other fellow volunteers experienced similar feelings of deep loneliness and despair. Some quit, others, quietly competitive like me, drowned our emotional pain in alcohol. Some, though, never made it home—a suicidal overdose took one, and another fell off a boat at night and drowned in the Gambia River. Then, while a large group of us were visiting the coast after a two-day training, a volunteer had a spinal injury while bodysurfing. Tumbling in the same wave beside him, I pulled him to shore. As he lay there in shock, all of us terrified that help would not come, he turned to me, weakly smiled, and said, “Mike, you have won.” The next day, an Army plane came and medevaced him to Germany.

When I returned to my post, sobered and shaken, I did not have the words in Wolof to explain what had happened. Haunted by my friend’s painful face, his damaged body, and his bitter words, I headed to the sandy paths beyond the village and sought refuge in the savannah.

Unable to articulate myself to the people around me, walking (like letter-writing) allowed me to make sense of what I was feeling and what I was experiencing. I found that the rhythm of my walking body stimulated a lyricism in my thinking mind, and from it a voice emerged, one that gave comfort as it gave order and meaning, Sometimes, meandering through the forests and grasslands, I would compose letters in my head to friends, and seemingly out of the ground beneath me, that voice would come to me. In time, I would learn to listen for that voice to tell the stories of my travels.

In those first months, I must have walked more than a thousand miles, exploring the surrounding lands and villages, footing it the 12 miles to the nearest town and back just to get my mail, and escaping from myself and the realities of life in the village of Darou Mouniaguene. But over time, walking became a ritual, a practice, and an education that I would use for years to come.

Walking alone in the otherworldly landscape of Senegambia, with its clusters of giant baobab and termite mounds, its wandering pilgrims and herdsmen, its mesmerizing monotony, I felt held by this ancient land, absorbed into it, emptied, my inner voice silenced. For tens of thousands of years, up into the era of the great kingdoms of the Songhai and Mali, people had walked through these forests once thick with trees. In awe, I watched the giant ball of the African sun roll along the horizon of wide-branched acacia trees, struck by the thought of my mortality, of my brief passage upon this earth.

Watching me come and go, some villagers began to give me the nickname tukkikat, a Wolof word that means “traveler” but is often used teasingly to refer to a “restless person,” or “a man always on the road.” But the elders and the chief of the village found my behavior troubling. They had warned me that it was dangerous to walk alone. Hyenas were a menace and roamed the savannah, following the herdsman with their cattle.

Though the elders did not directly speak of it, what they feared for was not just my physical safety but for my mental state, or rather, my vulnerability to the malevolent forces of the spirit world. So, they sent their sons to shadow me, visit me in the evenings, close my door at night, follow me on my walks, and come looking for me if they saw I was gone. Sometimes I must admit I hid from them, but I weep when I think of them watching over me, searching for me in the bush, caring for my lonely soul.

In the end, I would make it through those two years in the Peace Corps. I would eventually help the women of the village organize a community garden and plant fruit trees. I would absorb the language of Wolof so that it would come out of my mouth in my dreams, even years later. I would become a tukkikat, as they had ordained, traveling and writing about the world far and near, using those skills of observation and reporting I’d learned by writing long letters.

And I would return to this community of farmers twenty years later, a writer, reporting on the AIDS pandemic.

Arriving at the compound of the chief of the village, to my surprise, I was greeted by his son, now a head taller than me, the boy who’d once shadowed me in the bush. After going through the greetings, he sat on the floor before me, asking me to sit on his bed. With what Wolof I could remember and my translator, I told him how much I’d learned here, giving thanks to his father. But before I could finish, he let out a preternatural shriek, collapsed into his light blue djellaba on the floor, and sobbed uncontrollably. Like the intimate relationship of the reader and the writer, in my memories, he had felt his, and in his emotions, I had felt mine—and together, we remembered his father and those two years I lived in the village of Darou Mouniaguene.

Traveling into another culture, traversing other landscapes, sitting among prisoners practicing Zen meditation, interviewing patients dying of AIDS in Thailand, following sex workers into the streets of India, walking through abandoned neighborhoods in Gary, Indiana, I am still learning the lessons of the tukkikat.

In my writing, I am still drawn to subjects that demand immersion, risk, and sensitivity. I am still drawn to write about those who live on the margins of the world. And I am still drawn to write about those stories and places that can haunt my memory. But then, from the beginning, I learned that to write is to be haunted.

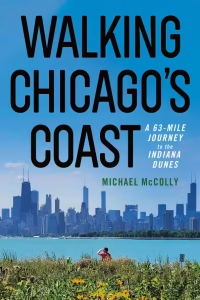

Michael McColly’s essays and journalism have appeared in The New York Times, The Sun Magazine, and The Boston Review. He is the author of The After-Death Room: Journey into Spiritual Activism, which chronicles his journey reporting on AIDS activism in Africa, Asia, and America. His newest work, Walking Chicago’s Coast: A 63-Mile Journey to the Indiana Dunes, recounts an improbable trek from his doorstep across Chicago’s metropolis, as he encounters its social and environmental inequalities, its history and his own, and the enduring wonder of what remains of its remarkable natural history.

Michael McColly’s essays and journalism have appeared in The New York Times, The Sun Magazine, and The Boston Review. He is the author of The After-Death Room: Journey into Spiritual Activism, which chronicles his journey reporting on AIDS activism in Africa, Asia, and America. His newest work, Walking Chicago’s Coast: A 63-Mile Journey to the Indiana Dunes, recounts an improbable trek from his doorstep across Chicago’s metropolis, as he encounters its social and environmental inequalities, its history and his own, and the enduring wonder of what remains of its remarkable natural history.